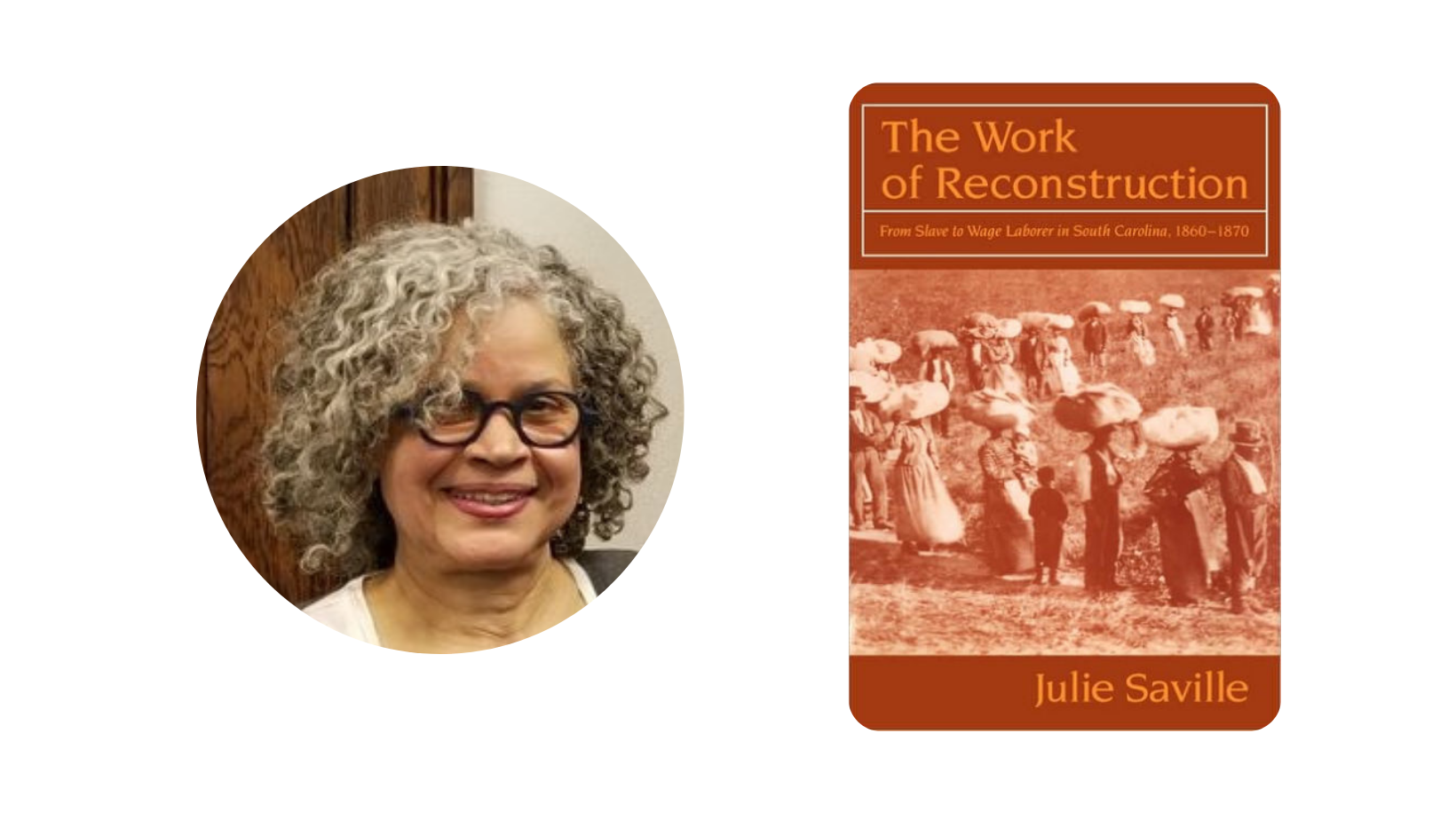

In remembrance of Julie Saville, Professor Emerita

The Department is sad to announce that Julie Saville, Associate Professor Emerita of History and the College, passed away on December 16. As a member of the History Department from 1994 to her retirement in 2017, Professor Saville was a leading scholar of slavery, emancipation, and plantation societies in the United States and Caribbean. She worked to demonstrate how everyday life, labor, and culture intersected with large-scale processes of enslavement and freedom, shaping those processes not only in the United States but across the Atlantic world. In the more than two decades that she spent in Chicago, she inspired generations of students to pursue such themes in Caribbean and US history. They learned from her to attend closely to the processes by which apparently deep-seated concepts of nation, citizenship, and race have in fact arisen out of the work and ideas of communities large and small.

Professor Saville spent her early childhood in Tuskaloosa, AL, during the Jim Crow years. At length her physician father and family were forced by violence to move out of the state to Memphis, TN. She then went on to do undergraduate work at Brandeis University, where, in the context of the late 1960s, she first decided to devote herself to historical work. After obtaining her PhD at Yale in 1986, she held appointments at the University of Maryland and the University of California, San Diego, before joining the University of Chicago in 1994.

Professor Saville was the author of The Work of Reconstruction: From Slave to Wage Laborer in South Carolina, 1860-l870 (Cambridge University Press, 1994) and a number of important papers tracing the experiences and trajectories of emancipation both locally and at scale. Most recently, she had been working on the political culture of the enslaved in the French Caribbean. Her work was distinctive in the attention it paid to how concepts of nation and citizen in the era of Reconstruction were bound up with experiences of enforced movement and subsequent post-emancipation politics. She showed how abstracted principles such as freedom, racial identity, and nationhood depended intimately on the works, travels, and thoughts of the formerly enslaved and freeborn people of color. She demonstrated this through a devotion to archival research as well as engagement with the scholarly debates of today. And she also maintained a strong commitment to engaging communities beyond the perimeters of the university, bringing the same dedication that she showed within our classrooms to adult-education initiatives in low-income neighborhoods beyond Hyde Park.

As that implies, for Professor Saville the everyday life of an African-American woman in elite academia was not something to be taken for granted: on the contrary, it was something to be curious about. She took care to notice the fine details, registering how careers that were often represented as emerging fully-formed from individual personalities were in truth dynamic, ever-shifting creations, produced collaboratively and always unfinished. And in this she saw “thematic parallels,” as she called them, with the histories of emancipation that she traced so carefully in the nineteenth-century past. Those who worked with her will remember how richly she herself personified that belief in the value of cooperative, humane, and creative interactions.

A Memorial Service for Dr. Julie Saville will be held on Wednesday, Jan 17, 2023 at 11:00 am at the Chapel of Elmwood Cemetery, 824 S Dudley Street, Memphis, TN 38104. Light Refreshments will be served following the service.

Professor Saville is survived by her sister, Nan Fifer, and a nephew, Alphonso Saville. The History Department extends its condolences to her family, friends, and loved ones.

Adrian Johns

Allan Grant Maclear Professor of History, the Conceptual and Historical Studies of Science, and the College, Department Chair

University of Chicago

Julie Saville joined the University of Chicago History faculty in 1994 and was among the founding generation of scholars of the Center for the Study of Race, Politics, and Culture. Her exceptional historical imagination, grounded in a keen sensibility to the complexities of human behavior infused both her writing and her work with students, enriching the life of the university. All of us emerged better historians, with a better understand of the complexities of the human behavior from having known her.

One imagines that her special sensibilities and insights were nurtured by her work early in her career on two monumental editorial projects that arguably recast the empirical basis and possibly the conceptual approaches to studies of the African American experience: the Frederick Douglass Papers initiated by John Blassingame at Yale University on which Julie worked as an assistant editor and two volumes of the Freedmen and Southern Society collection at the University of Maryland with its founding director, Ira Berlin. Julie co-edited what is arguably one of the most influential volumes of the Freedmen project, The Wartime Genesis of Free Labor: The Lower South. Her stunning introductory essay later published separately and much cited, no doubt formed the basis for her dissertation and subsequent book, The Work of Reconstruction: From Slave to Wage Laborer in South Carolina, 1860-1870 (Cambridge UP, 1996). The editorial work amounted to the creation of an archive of materials pulled together from and unearthing and assembling hitherto seemingly unrelated documents from a sprawling, diverse array of federal records depositories. In short, the Freedmen’ Project effectively recovered a hitherto hidden archive of the war and of black Americans’—free and enslaved—crucial role in it. Over time it opened areas previously closed to and thus invisible to historians of this subject and era, thus generating a host of new work. Assembling and editing the Freedmen’s Papers was undoubtedly one of the most productive ventures in American History during the late 20th century; it quite literally redefined the historiography of a crucial historical era and subject.

Julie’s The Work of Reconstruction-- deliberately understated, non-polemical--carefully and respectfully rendered its subjects lives and thought, and thereby illuminated and re-conceptualized key developments not only of the war and post-war South’s history but of American labor and political history more broadly. Unlike previous work on the subject rather than simply evoking, it deeply engages at an empirical level the notion of a “moral economy,” a world view, and thus the fundamental motivations of freedpeople themselves. For example, rather than engage earlier polemics about whether ex-slaves responded to the wage much as white workers had or acted out of a necessarily different world-view, Saville builds a portrait of freedpeople’s social life—family, kinship, community, and the world-view that was their legacy from slavery--in order to show how their responses to both the material and non-material incentives of the new work arrangements of freedom were shaped in extremely complex ways, by both past experience and an anticipated new order. In short, she historicized what was in danger of becoming essentialized by opposing, historically static interpretations. In short, like other people, slaves were neither innately responsive to wage incentives nor unresponsive; rather they became one or the other through specific historical experiences.

Equally important, Saville provides what was then a groundbreaking discussion of Reconstruction politics; one in which political activities and choices run like a bright thread through a richly texture fabric of social and economic life. Indeed, the chapter on politics may well be the most original and brilliantly insightful section of the book. We are shown how this amazing post-emancipation political mobilization could come about, how it was built up from more fundamental relations of kinship, family, community, labor sharing, and other mutual aid. It is certainly one of the best discussions of black political mobilization during Reconstruction, and arguably the most underappreciated. In sum, Work illustrates how social, economic, and political life must all be part of the same narrative, if any one of these are fully to be understood. After reading Saville’s Work of Reconstruction, no one could credibly write about labor processes and political processes in quite the same way again—at least not and still be taken seriously.

Julie would move on from studies of the U.S. South to examine comparable developments in the post-emancipation French Caribbean. Although her timetable on this new area of research would soon be compromised by her debilitating illness, she succeeded in passing along that mission to many of the graduate students she mentored and those undergraduates as well as graduate students fortunate to have taken her courses on comparative studies of race in the Atlantic world. The long-running CSRCP “Colonizations” sequence is one of the fruits of her intellectual contribution to the undergraduate curriculum. Evidence of the continuing impact of that course are the graduate student assistants now drawing on the insights of Atlantic World studies to pursue similar topics in the Pacific World. Thus, the legacy of Julie Saville’s insights will continue to shape these fields of race and labor studies deep into the future.

Tom Holt

James Westfall Thompson Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus

University of Chicago

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO